Submitted by Christine Georgiou on Thu, 02/04/2020 - 09:03

A smartphone app to map epidemics that was developed in this department a decade ago is seeing a resurgence of interest because of the COVID-19 outbreak

The co-inventor of the ‘FluPhone’ app – Professor Jon Crowcroft, the Marconi Professor of Communications Systems here – has had approaches from healthcare professionals and academics in Australia, Canada and countries in eastern and central Europe, wanting to know more about it.

And he’s also been contacted about it by NHSX, the arm of the NHS tasked with seeing how the latest technologies can be employed to improve health care.

The research app was originally developed by Jon and his colleague Eiko Yoneki, a Senior Researcher in the department, in the wake of the 2009 global Swine Flu (H1N1) outbreak. The aim was to collect smartphone location data and use it to measure social encounters between people, and so model and predict how illnesses like Swine Flu were passed between individuals.

Mapping human contacts

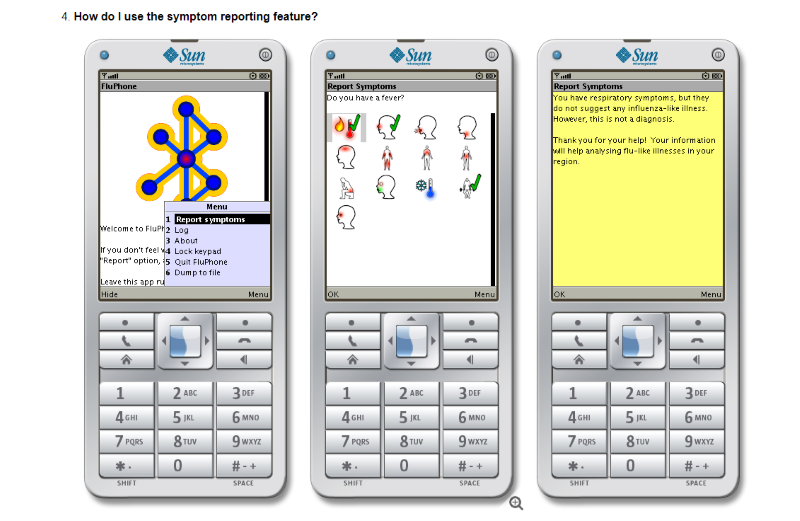

This idea had developed from Jon’s and Eiko’s work in mapping human contacts to measure the ways people met in the real world. As part of that, they had built an app employing the short-range radio capacity of mobile phones (which is what bluetooth headsets to use) to detect the presence of other people coming within close proximity of the phone.

John Edmunds, a noted epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, heard them talk about their work. His research interests are in designing effective and cost-effective control programmes against infectious diseases “and he told us it would be very useful to harness the app for measuring epidemics.”

Smartphone location data could provide crucial intelligence about how the pandemic is evolving and help us develop evidence-based strategies for coping with such outbreaks.

Jon Crowcroft

So they set up a pilot study and ran it for three months in Cambridge in 2010. Several hundred volunteers were recruited and asked to download an app onto their phones that would collect information on their social encounters and anonymously record how often they met other people. “It was a small study,” says Jon, “but it did effectively prove the concept.”

And the concept is now of great interest again – as it should be, he says. In his latest blog post for the Turing Institute, where he is also a Researcher at Large, Jon argues that the COVID-19 pandemic “is an urgent opportunity for scientists, the NHS and other health services around the world to use smartphones and their owners to gather valuable data on an unfolding pandemic.

“This data,” he adds, “could not only provide crucial intelligence about how this pandemic is evolving, but also help us organise against the onslaught and develop effective, evidence-based strategies for coping with future outbreaks.”

The original FluPhone project aimed at doing both these things. Its two goals were to enable epidemic modelling with precision, and to trace contacts.

Finding the parameters of the epidemic

“If used now, it could help us find the parameters of the epidemic and allow us to predict its growth,” Jon says. “With the FluPhone application, people would register with their age, gender and contact info, and then we could measure all the encounters they have with other people who have the app. We could then use that data to map the fraction of the population that is infected and how many of them in turn infect other people.”

The app would be particularly beneficial, he says, in identifying those folks who come into contact with an infected person, become infected themselves and subsequently spread the virus to others without knowing that they have done so because they are asymptomatic. “Using this app, we could discover them,” he says, “when without it, it’s very difficult to do so.”

And vitally, the app could also map the impact of the disease among children. Back in 2010, there were initial concerns – from a University research ethics committee – about recruiting children for the pilot study. But the levels of user privacy built into the system subsequently reassured them and the researchers were allowed to invite children over the age of 12 to take part.

And this is key because “children are very important in epidemics,” Jon says. “In influenza outbreaks, for example, it is very commonly kids who spread the infection between households.”

Though they don’t appear to be susceptible to COVID-19, it may well be that in fact they are. “There is already data on COVID-19,” Jon says, “suggesting that as many as half of children who come into contact with an infected person become infected – and infectious – themselves, but without showing any symptoms.”

If we are going to accurately predict the spread of viruses like COVID-19, we need to have more accurate transmission metrics, he argues, than a standard multiplier that suggests that one infected person will, on average, infect two others.

“So it really matters for us to know if the teacher is going to catch the virus from the children they teach, or whether the children are going to catch it from the teacher and then take it home where others in the household will be infected. Our app would really help with this.”

Another potential use of the app would be in providing data to help us judge how effective interventions like social distancing / quarantine / lockdowns might be in preventing the spread of the disease.

Technological data gathering to track COVID-19

Some Asian countries, of course, have been using technological data gathering to track the disease and try to halt its spread. In South Korea, authorities were granted access to residents’ mobile phone records to round up and test the contacts of those displaying symptoms, and quarantine those found to be positive. While this was quite invasive of residents’ privacy, it was also an example of an intervention that has been remarkably successful in stopping the spread of the virus.

And Singaporean authorities have also been using an app – strikingly similar to the FluPhone app – to monitor the cases of COVID-19. “And they were able to do so without being overly intrusive,” Jon says. “When people developed symptoms there, they were asked to self-report – in other words, to send in the records from their app so that the health authorities could track and inform their contacts. They in turn were offered testing to discover if they had the disease.”

And now there is a similar app in the UK, which has been developed by King’s College London. It enables people to report symptoms of COVID-19 so that the progression of the disease can be tracked in real time.

Jon is delighted to see the idea of harnessing smartphone technology in our battle against COVID-19 gaining traction.

“And the need for such an app is not over, it is only just beginning,” he says. “After the peak, which will be in the next three to four weeks, we’ll still need ways to track the illness because the majority of the population will not be immune. So when future cases turn up, we must be able to track their contacts and quarantine those who test positive, otherwise the disease will break out all over again. So apps like FluPhone will have importance for some time to come.”