Submitted by Rachel Gardner on Tue, 29/10/2024 - 13:15

How is medical misinformation being spread online? Who is spreading it? And can we develop tools to reduce the harm caused to patients by conspiracy theorists and scammers selling fake cures?

Those are the questions being explored in a new project just getting underway in our Security Research Group.

'Medical Misinformation – Understanding the Spread and Monetisation of Fake Cancer Treatments' has just won funding from the Google Academic Research Awards Programme. This is a new scheme that provides support to advance research in key areas of computing and technology.

The project will focus on cancer. False and harmful content about it is increasingly widespread on social networks where users can be found touting fake therapies that are at best ineffective and at worst poisonous. But since the pandemic, security researchers' attention has been diverted away from cancer misinformation and towards the spread of fake news on Covid and Covid vaccines.

The project will focus on cancer. False and harmful content about it is increasingly widespread on social networks where users can be found touting fake therapies that are at best ineffective and at worst poisonous. But since the pandemic, security researchers' attention has been diverted away from cancer misinformation and towards the spread of fake news on Covid and Covid vaccines.

Now, our colleagues say, we need to put cancer misinformation back in the spotlight. "Recent research has found that around 70 per cent of people with cancer encounter medical misinformation promoting fake cures and treatments," says Alice Hutchings, Professor of Emergent Harms here.

And this puts them at significant risk of harm as "People with early stage cancer who ignore medical advice in favour of more alternative treatments may then progress to later stages that could otherwise have been preventable. This means they may die from completely curable diseases."

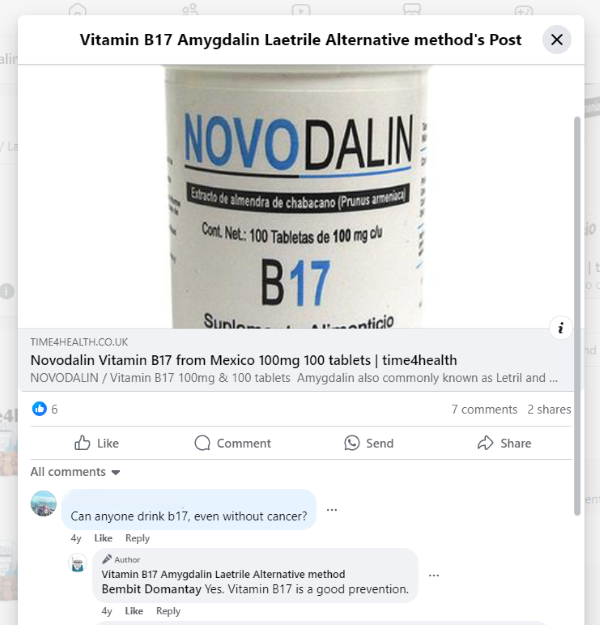

Image, right: A social media post advertising Laetrile / so-called 'Vitamin B17', as a cancer therapy. The charity Macmillan Cancer Support points out that it is not a vitamin and says there is no medical evidence for claims it can control or cure cancer. They also warn it can have serious side effects including cyanide poisoning. The sale of Laetrile has been banned by the European Commission and by the Food and Drugs Administration in the USA.

To try and get to the root of the problem, Prof Hutchings and PhD student Anna Talas will spend a year exploring different forms of cancer misinformation and how it's spread.

They will use AI tools to explore how many users are responsible for spreading the false information and how lucrative it is for the criminals who sell bogus therapies.

People with early stage cancer who ignore medical advice in favour of more alternative treatments may then progress to later stages that could otherwise have been preventable. This means they may die from completely curable diseases.

Alice Hutchings, Professor of Emergent Harms

The aim is to inform ways that online platforms — including those operated by cancer charities — can detect and prevent the spread of such misinformation. The researchers hope that in doing so, they can make it easier for people with cancer to fact check what they’re reading, and find trustworthy and reliable sources of information and support.

"I'd like this research to have a real-world impact," says Anna Talas. For her PhD, she is researching vulnerabilities from both human and technical perspectives, and the use of privacy-enhancing technologies to help people at times when they are particularly vulnerable.

"Research has shown that people who are going through emotionally difficult times are more likely to fall for scams in general," she says. "This can also be true with medical misinformation as you may see an advert for a 'miracle cure' that promises to fix all your problems at a time when you’re in such a desperate state, you’re willing to try anything."

However, while there’s a clear need to combat such misinformation online, doing so is not going to be easy as Anna and Alice have learned from the cancer charities they are working with.

Research has shown that people who are going through emotionally difficult times are more likely to fall for scams in general. This can also be true with medical misinformation as you may see an advert for a 'miracle cure' that promises to fix all your problems at a time when you’re in such a desperate state, you’re willing to try anything.

PhD student Anna Talas

"In our conversations, they’ve told us that more people are expressing scepticism about conventional medicine since the covid pandemic," Anna reveals. "It appears that people who got into all the conspiracy theories around covid are also less likely to believe in conventional treatments for other diseases, such as cancer."

Anna wants to know how users respond to medical misinformation online. "Do they alert other users that the content is misinformation? If so, how is this received by the online community?"

Studying issues like this may, it is hoped, help the research team to develop relevant ways of intervening to combat the spread of the fake information. "And we need to do this," Anna says. "When we hear about scams, we always think 'Oh, I'm not going to fall for one of those'. But unfortunately, the truth is that we’re all at risk."