Submitted by Jonathan Goddard on Fri, 03/05/2019 - 15:59

EDSAC ran its first successful program on 6th May 1949, making it the world's first fully functional stored-program computer.

One of the world’s earliest computers was born 70 years ago at the Computer Lab. The EDSAC – Electronic Delay Storage Automatic Computer – was developed at the University of Cambridge after the Second World War, and ran its first successful program on 6 May 1949.

EDSAC was the first computer in the world to be fully operational and practical for general use. An earlier stored-program computer known as “the Manchester Baby” was built at the University of Manchester 11 months before EDSAC, but it was experimental rather than a practical scientific tool.

By comparison, EDSAC was fully functional from its first day, operating as a complete system that did not need resetting after each calculation.

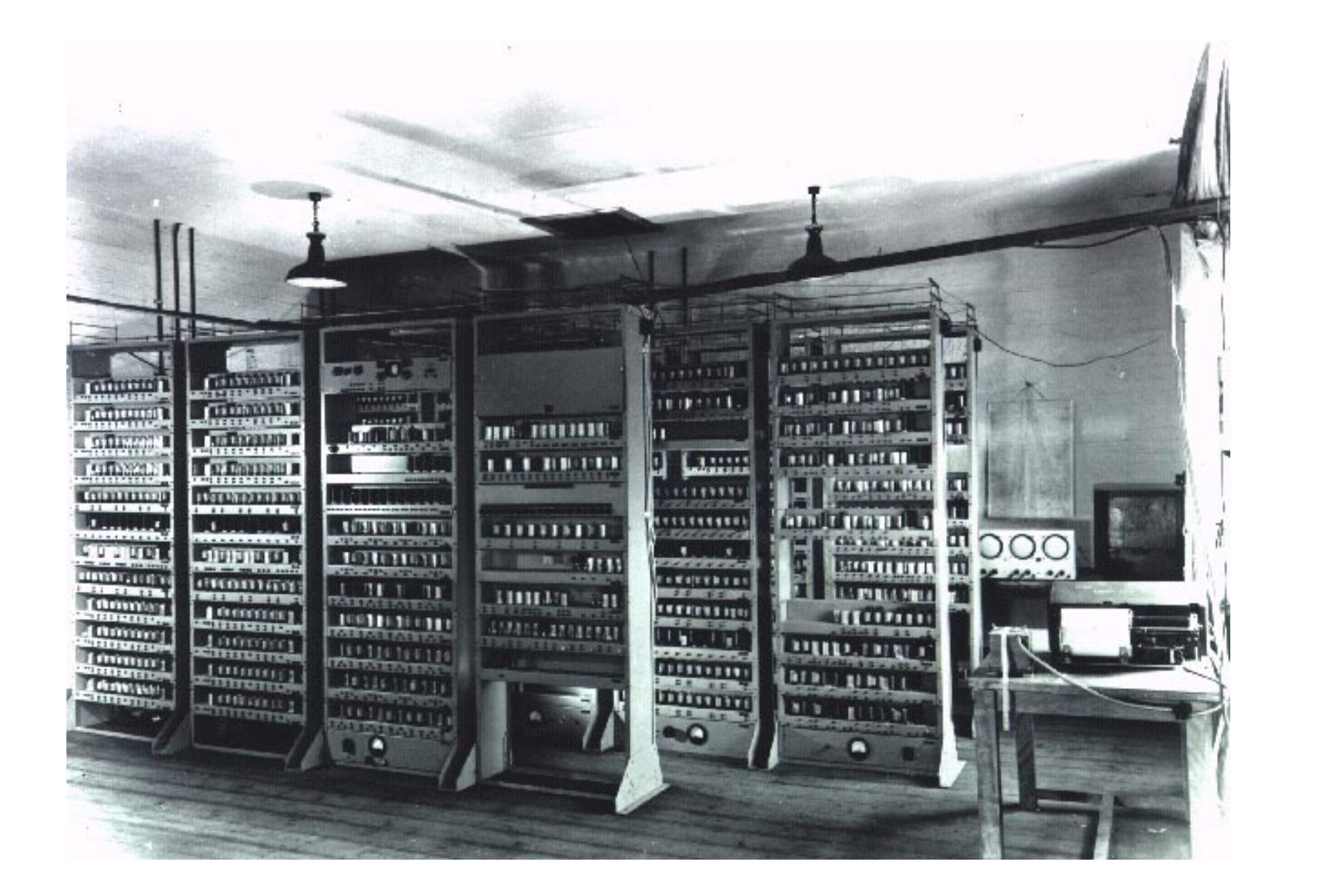

The EDSAC was a huge machine, which filled a whole room at the University’s Mathematical Laboratory, a precursor of the Department of Computer Science and Technology. At the time the Mathematical Laboratory existed to support the University’s scientific and technical departments by providing computation and calculation. After its initial success, EDSAC was quickly adopted by the wider University for supporting research. The very first scientific paper to be published using computer calculations was a genetics paper by RA Fisher, using EDSAC.

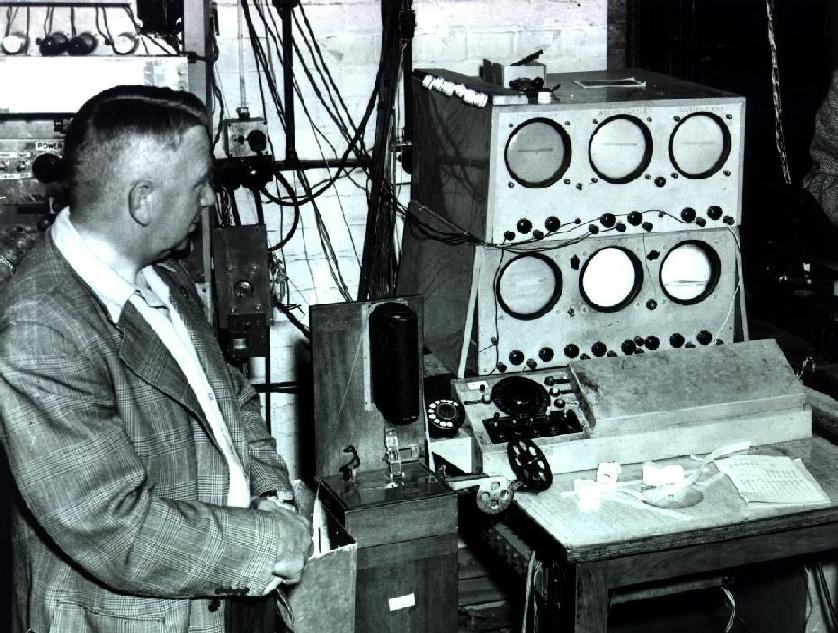

A programmer works on the machine

Maurice Wilkes and the Mathematical Laboratory

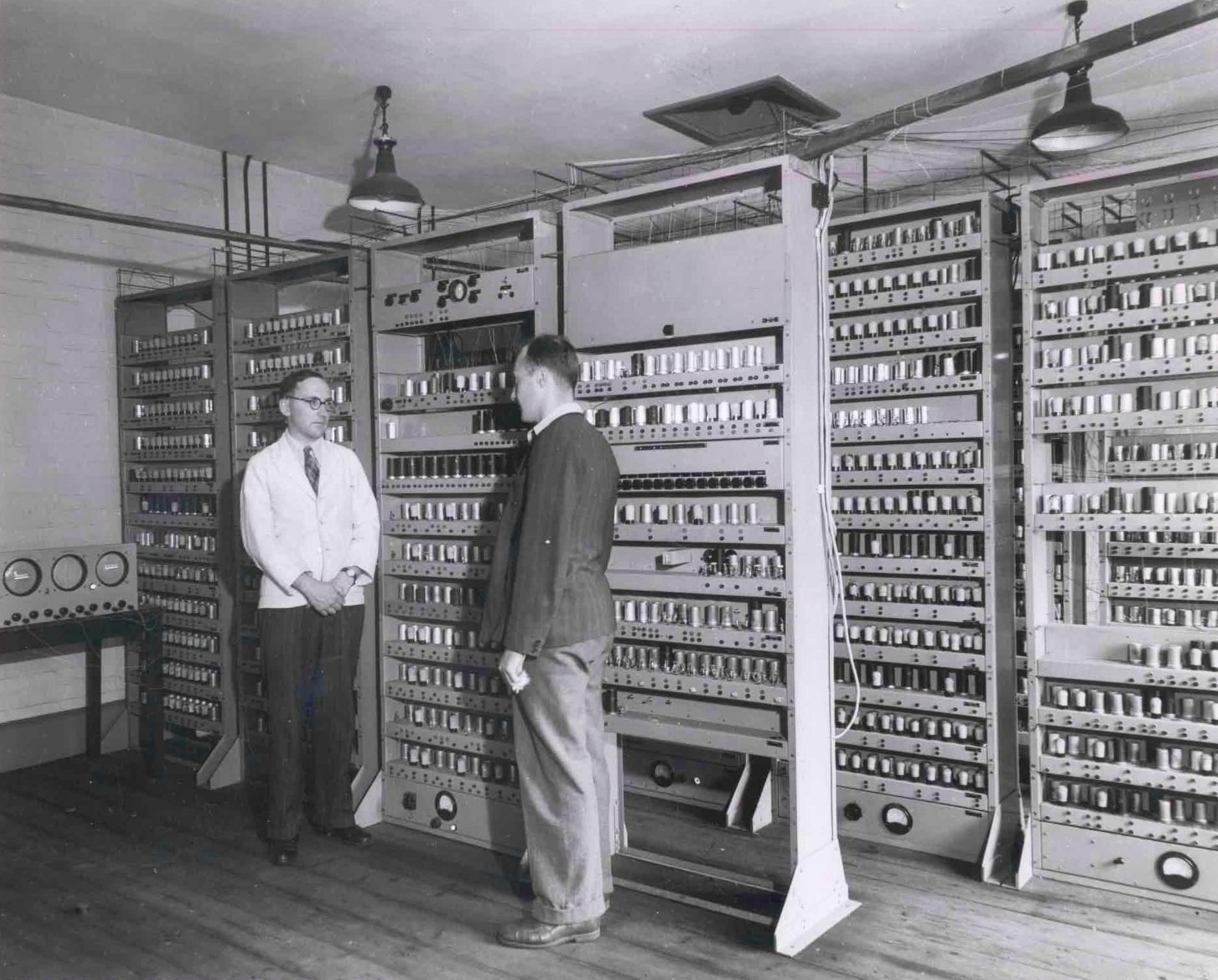

In September 1945 Maurice Wilkes was on his way home from war service, having worked in radar and electronics throughout the Second World War. He was appointed Head of the Mathematical Laboratory in Cambridge, and his remit was to establish a department that could provide computing expertise to the University and support its scientific research.

Wilkes studied the latest developments in computing machinery, especially from wartime advances made in the US, and gathered a team of experts together to form his new lab.

Maurice Wilkes (left) with EDSAC during its construction

In the 1940s, researchers had to use mathematical tables and mechanical calculators to conduct time-consuming calculations. Wilkes’ vision was to use new computing technology to develop machines that would assist scientists, engineers and mathematicians in their work. He hoped to provide Cambridge researchers with faster tools that simplified complex calculations.

Wilkes also wanted the machine to be accessible by, and useful to, as many researchers as possible. Earlier experimental machines had only been usable by a small number of technical experts. Wilkes used simple, conservative design to enable his computer to have the widest possible practical applications.

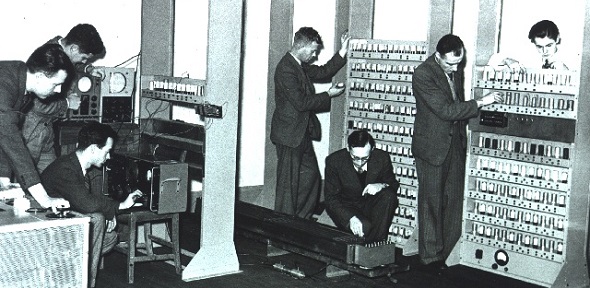

Pioneers working at Cambridge's Mathematical Laboratory in May 1949

How did EDSAC work?

EDSAC was based on thermionic vacuum valves, which were widely used in early computers, and in the advanced radar systems that Wilkes had worked on during the war. EDSAC’s 3,000 vacuum valves were arranged on 12 racks. The vacuum tubes were filled with mercury, which provided the computer’s memory.

EDSAC operated for 35 hours a week, for nine years, and was housed in University buildings in central Cambridge. During the working day there were engineers on hand to provide technical support when problems arose. Researchers who gained special approval could work on the computer overnight, but any technical support requests had to wait until the morning to be investigated.

EDSAC consumed 12KW of power, and was hosted in a room measuring five metres by four metres. This early computer could execute approximately 650 instructions per second. Modern computers can compute millions of times faster, but in the late 1940s and 1950s EDSAC offered a massive improvement on what was possible at the time. EDSAC is said to have increased productivity by 1,500 times, and revolutionised scientific research at the University of Cambridge. Problems that had previously been impossible or impractical to attempt could now be solved.

The development of EDSAC

EDSAC was superseded by a more advanced machine, EDSAC 2, in 1958. EDSAC 2 was built by Maurice Wilkes and the same team who had created the original EDSAC.

A significant number of researchers benefitted from the revolutionary computing power of EDSAC which they were able to take advantage of at Cambridge. This included the winners of three Nobel Prizes: John Kendrew and Max Perutz (Chemistry, 1962), Andrew Huxley (Medicine, 1963) and Martin Ryle (Physics, 1974). They all acknowledged the role EDSAC had played in their research in their Nobel Prize acceptance speeches.

How EDSAC and Cambridge computing changed the world

May 1949 marked the beginning of a new era in human activity: the birth of everyday computing. The successful operation of EDSAC ushered in the use of computers as everyday tools. Prior to this, computers had only been used experimentally or to solve specific problems, such as Turing’s machine for breaking the Enigma code. EDSAC was the first computer to provide general computation and practical support for mathematical and scientific calculations.

The first course in Computer Science at Cambridge started in 1953, and used the EDSAC.

This film of EDSAC was made in 1951, and includes an introduction and voiceover by Maurice Wilkes from 1976.